The Public Garden—a 24-acre green emerald in the heart of Boston—is a true gem. Created in 1837 and completed in 1856, it’s America’s first public horticultural garden, built on what was originally a salt marsh where rope makers used to dry their lines. The garden features a monument that’s accepted as the first equestrian statue of George Washington, a walkway that’s often falsely referred to as the shortest functional suspension bridge open to public crossing, and two statues sculpted by Daniel Chester French. He’s also known for having sculpted the lions and the bronze doors at the Boston Public Library, and, as an afternote, the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

The Public Garden also features a man-made lagoon. Since 1877, tourists have paid a nominal fee to tour the lagoon in a long boat, silently propelled by an enormous swan.

The Public Garden is one of my favorite spots in the city. And I always make a special visit early in the spring, when the Parks & Recreation Department drains the lagoon all the way down to the dirt. They fix whatever winter damage the masonry and water system suffered, and also run machines around to remove matted vegetation and re-grade the bottom. It’s a once-a-year opportunity to take in views of the Public Garden from locations that in warmer weather would cost you a pair of wet trousers and an angry ejection from the park.

My 2012 lagoon constitutional was productive on two fronts. First, I took and passed the live version of the Voight-Kampff test, by discovering a red-eared turtle flailing on its back in dry sand, and then reaching down and righting it. I definitely saved its life. If I’m ever in a sticky situation in the Public Garden where the difference between life and death hinges on the brave intervention of a hamburger-sized turtle…I like my chances.

A bit further on, I spotted something shiny:

And there you have reason number two for taking a stroll around the dry bed of the Public Garden lagoon. The lagoon is only three to five feet deep, but that’s more than enough water to enforce a strict “You Drop It, You Lose It” policy for swan-boat riders.

The camera was deeply embedded, so that its lens was flush with the surface. Any notion that it might have been lost in recent weeks was dismissed when I pried it out.

Its back was a lump of rust and corrosion. I wondered if its memory card could still be functional and its photos recovered, after what must have been a few months underwater and a winter of repeated icing and thaws.

I decided that it was worth finding out. I tossed the remainder of my snack to grateful squirrels gathered at the bank of the lagoon and dropped the muddy camera into the empty cellophane bag. Had the camera still been underwater when I encountered it, I would have transported it home in water as a precaution, to prevent further damage from mold, mildew, and evaporation. As it was, I was only using the bag to prevent my jacket pocket from getting all mucky.

Camera autopsy

I got home and went to work. The camera was a Kodak EasyShare M341. I actually had a battery and charger for that kind of camera in my hardware library, but the thought of reviving this camera from the land of wind and ghosts was laughable. I just didn’t want to damage the real prize: the memory card.

The door to the battery/card compartment was jammed tight. I left it in a water bath to soak overnight, and then attacked it with a drawer of dental tools. I pried the door open and then managed to disengage the retaining claw enough to tease the card out.

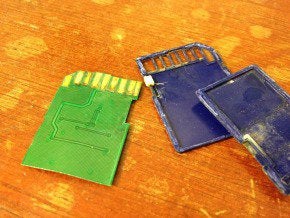

It was filthy with rust and mud. I used an X-Acto knife to pry apart the card housing, exposing the wafer within. Some attention with steel wool restored the mustard-brown metal contacts to a bright—and hopefully electrically conductive—shine.

I scrubbed the halves of the card housing clean with a toothbrush, allowed everything to dry, and then reassembled the card with tape. I wasn’t going to risk my brand-new MacBook’s internal SD slot on this mud-puppy. Instead, I rummaged through a drawer until I found a cheap card reader I could afford to lose. I inserted the card, plugged the reader into my MacBook, and behold!

…Nothing. It was dead as a cod. My Macs and Windows machines couldn’t even recognize it as a functioning electronic component.

It was time to call in the Ghostbusters.

Patron saints of lost causes

I emailed a contact at DriveSavers. “Interested in a challenge?” I asked.

If you’ve lost files that are truly important, you want to bring in DriveSavers. They will saw into the cold blob of charred, slagged metal and plastic that was once your $1400 laptop until they encounter something that was once a hard drive, or an SSD, and then set their clean-room minions to work.

DriveSavers responded to my email with vigor, and a next-day FedEx airbill.

A few days after I sent off the card, I got an indication of just how intensely DriveSavers operates. “Do you happen to have the card label?” they asked. “We’re going to order some parts and it’ll help if we know the make of the memory card.”

Replacement parts. And not for an ’88 Gran Fury, but for a postage-stamp-size memory card. That’s hard-core.

A few days later…success! DriveSavers recovered over 140 photos and two video files. According to their forensic report, the lagoon water had corroded the microconnections between the card’s memory and USB controller chips and the board. A DriveSavers engineer, working in a cleanroom, cleaned the contacts and re-soldered the faulty wiring.

In addition to the recovered photos and videos, they were also able to find a evidence of a batch of documents that had been on the card but long-deleted. They had the documents’ filenames, though the files themselves were unrecoverable.

The biggest surprise of the report? The camera’s time of death. I’d discovered the camera face-up in the mud, in plain sight. I had assumed that it hit the water sometime during the 2011 season. But the most recent photo on the card had been taken on the afternoon of June 24, 2010.

Given that it was clearly taken by someone on a boat, at a spot on the water that matches up with the spot in the lagoon where I found on the camera…yeah, I’m guessing this was the last photo this Kodak ever snapped.

This camera had spent two whole seasons under water and mud. It had gone through two complete winters of freeze and thaw. It had probably been pecked at by diving ducks more than once. And DriveSavers had recovered what appeared to be all of its photos.

A clearly giddy DriveSavers team described the rest of the images to me over the phone. Lots of photos of a pair of little kids. Photos of some grandparents. A graduation video. Shots of a hotel pool and a kid at a commuter rail station.

I couldn’t wait to see the photos so that I could begin the work of trying to identify its owner and reuniting him or her with the pictures. But DriveSavers has strict privacy policies. This wasn’t my memory card, and these weren’t my pictures. They were the private property of the owners of the camera. DriveSavers’ security policy forbade them from releasing the card’s contents to me.

They could only send me some sample photos, in which faces weren’t visible. OK, fair enough.

In any event, it was clear that whoever had lost this camera would want to get these photos. The report described a lot of nice, once-in-a-lifetime family moments.

I set about trying to find the owners with what little data I had. My first clue was in the deleted document filenames. Several of them referred to the same jewelry design firm in Boston. I found the company online, and after exhausting all of the public means of contacting them electronically, I yielded to a final act of a desperate man: I called the business and spoke to humans.

Nobody there remembered losing a camera in the lagoon.

Okay, how about the camera’s serial number? It had been embedded in the EXIF information of each photo. This, too, led to a dead end: No response from Kodak.

Well, maybe after the family lost their camera, they kept shooting photos with a phone. I performed image searches, looking for pictures that were shot on that afternoon and either geotagged in the Boston area or manually tagged with likely keywords. Like “Boston” or “Public Garden” or “Never Let Your Kid Borrow Your Camera On A Boat.”

Or maybe they blogged about losing a camera in Boston? More searching.

Nope and nope. My search-fu was weak that day, friends. And of course, the city and the operators of the swan boats don’t have records of people losing things in the lagoon.

Oh, well.

So there it is. Look at these pictures. If you think you recognize these people, or if you are these people…contact us with some kind of evidence and we’ll pass your contact info along to DriveSavers.

Your pictures are ready. Free of charge. Normally, DriveSavers charges a flat $690 fee for recovery of data from a card 8 gigs or smaller. In this case, the only fee they’re receiving is this rusted-out camera corpse. They’ll add it to their collection of crushed, burned, melted, and waterlogged hardware, each a lingering memento of somebody’s Very Bad Day.

For everybody else, there are two takeaways from this experience:

1. There are almost no limits to what can be done to recover data from a broken storage volumes. Don’t write it off until you’ve let a company like DriveSavers take a crack at it. The cost may be steep, but you can always make more money. Re-shooting your kid’s birth requires a TARDIS and that’s much more difficult to arrange.

2. There’s a reason why your camera comes with a wrist strap. Use it!